A supply gap is looming in the metals market. And nothing tells this story better than copper, which has always been a bellwether commodity. There’s been an obvious transition point in the last 18 months where it’s moved into a medium-long term structural deficit, largely driven by its pivotal role in enabling the energy transition economy.

Copper is intrinsic to electric vehicle (EV) manufacture and charging infrastructure. With the UK, Israel and Germany, among others, stopping the sales of new fossil-fuelled vehicles by 2030, copper demand is expected to exceed forecast supply and prices to rise.

According to figures from GlobalData’s Mining Intelligence Centre and The International Copper Association Copper Alliance (2030 data is estimated based on trend) we’ll need another four million tonnes of copper in 2030 just to serve the light vehicle EV market. So, what does this mean for mining, and how can miners to rethink their expansion plans for step-change production increases?

“We need to look for accelerated ways to bring additional tonnes to market and new mines into production if we’re to have any chance of avoiding this supply gap,” starts Simon Yacoub, Vice President, Resources for the Americas at Worley.

Modern-day projects will need to be driven from a speed-to-market perspective to meet future demand. “This will require some retraining of our industry muscle memory from the last decade, where the lowest cost of entry defined the path to acceptable value,” says Yacoub. “Nowadays, with strong commodity prices and supply-side constraints, this value equation has rebalanced.”

Reintroducing lean integrated project delivery to mining

One way of achieving this pivot and delivering improved value is through a lean integrated project delivery (IPD) model.

“Lean IPD is not a new term for the mining industry. In the late 1990s and again pre-GFC, it was a common approach in certain parts of the market. But somewhere along the way, we stopped applying its principles to the modern day,” says Yacoub.

“From a productivity and delivery efficiency perspective, the mining industry has stagnated for several decades as a result of overly complex supply chain processes, assurance associated loops of redundancy, and general mistrust between project delivery stakeholders, all of which affect the length of time it takes to deliver projects,” he adds.

“The lack of trust that is prevalent in project development and delivery is also contributing to cost, schedule, and quality performance issues. This means that for the first time in a long time, supply-side pressure is making it difficult for miners to close the supply gap.”

So how can the mining industry meet the demand for copper, and other new energy materials, and deliver them through a streamlined, lean IPD system?

Driving superior owner value in the business case.

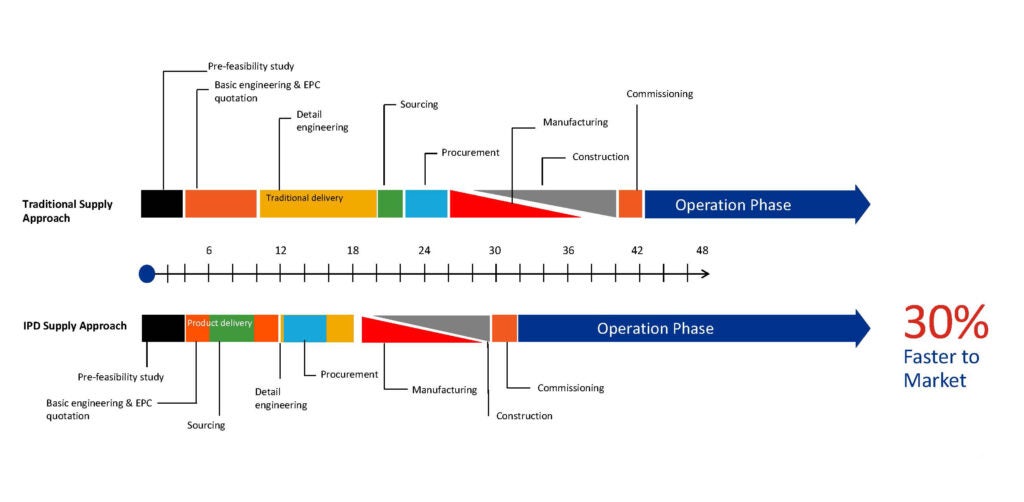

Lean IPD challenges the key concepts in the linearity and sequencing of traditional project development approaches. Instead, it parallels project activities, making key decisions happen earlier in the development timeframe, using risk balanced approaches that encourage innovative solutions.

“Typically, engineering sits on the critical path to create something to a precise specification. Taking that specification, we run a procurement process, have it fabricated, installed, commissioned, and passed into use,” explains Yacoub. “It’s very linear and sequential.”

Lean IPD turns this around and reduces the impact of engineering on the critical path.

“Our industry contains excellent empirical and experiential datasets on key equipment throughout minerals processing flowsheets, so we know within the realms of relativity what key pieces of equipment are needed early in the development cycle.”

“Purchasing, rather than engineering, equipment can help achieve faster speed to first metal. The temptation to bring absolute precision to key equipment theoretically has an optimised value but does not consider the opportunity cost and NPV impact of delayed metal to market.”

“By challenging the ‘specify, prequalify, 3 bids and a buy’ approach, a project can implement a range of early engagement activities to deliver equipment and works contracts aligned to speed to market objectives.”

The same can be said for construction. Currently, we sequentially tender construction, issue construction packages, then mobilise. But there is a more collaborative way to work with construction partners by bringing them in earlier to the project delivery equation. They can work faster and have a say in how the engineering is defined, specified and done with the end in mind.

“This is not without risk,” adds Yacoub. “But it’s a risk that is relatively straightforward to manage, and the rewards can outweigh some of the cost inefficiency that is created through the traditional process.

“For example, the project drivers, key success factors and enablers must be articulated and demonstrated by all parties from the outset. This maintains a focus on mutually beneficial outcomes and prevents self-interest. Again, trust is key. It’s hard won, but easily eroded by self-interest from any participant. Therefore, it needs a heightened level of executive involvement to set the course.”

Double digit cost and schedule improvement

The lean IPD model has proven its value creation potential across several sectors. “One example is our confidential work with a West Australian miner to increase iron ore production by more than 100mtpa… with three years to do it.”, said Yacoub.

“This meant production needed to increase by over 180%. Ramp up had to be in the months, not years, and name plate had to exceed 100%. Analysts were sceptical. However, by setting ambitious stretch targets, bringing forward vendors and contractor engagement and aligning stakeholder relationships, we were able to improve on historical benchmarked cost and schedule metrics by 20-30%.

“If we evaluate what that 30% first metal to market looks like through the lens of rising commodity prices for new energy materials – and the ability to meet the market a lot faster – you can see the benefit that this approach provides to an owner from a net present value perspective,” he adds.

Metal to market is increasingly important as the supply gap for many commodities widens. But the ESG (green) aspect is now equally important as the financial (lean).

The greening of an industry

The levelized cost of energy from photovoltaics and onshore wind already matches the cost of energy generated from traditional carbon-based energy sources.

However, the production of zero-carbon metals is not an equation that only relates to decarbonising the metal stream. While there is value in energy efficiency improvements, efficiency alone will not get us to net zero. There is a more sophisticated lens that we need to evaluate low carbon metals through.

“Our industry is known to be a slow adopter of technology and now it faces more pressure than ever to rethink this approach; particularly as ESG and decarbonisation become more of a holistic driver of value,” says Yacoub.

Technology will be a prominent enabler of a sustainable mine. But we must plan for technology jumps. Visibility into the future of emerging technologies and evolving economics is difficult but critical.

“Miners are accustomed to solving technical problems through incremental gain and collaborating to drive optimised cost solutions. This is different, as it’s a fundamental shift, rather than an incremental change. Our regular problem-solving ecosystems do not work as effectively without this level of clarity, so we need partnership approaches to work together to solve complex challenges. Mining companies must find the right partner to help co-create energy transition roadmaps and navigate the complex challenges in a way that turns conundrum into solvable problems and possibilities,” said Yacoub. “There are and will be, many ways to decrease energy intensity and the associated carbon emissions. These range from highly mature Horizon 1 solutions through to early research solutions that will become ready for application in Horizon 3.”

For example, a strong element of electrification will form part of the decarbonisation journey.

“Owners across the world are currently exploring electrification and the greater use of electric vehicles (EVs), which can remove up to 50% of a mine site’s emissions. But we’ll need to plan this transition over decades as we wait for technology to catch up, while supporting miners on a logical transition of fuel reduction, displacement and elimination.”

Collaboration and trust will accelerate production

Delivering lean IPD projects will provide profound benefits to our industry while also benefitting the environment, communities, economies and contributing to our global commitments to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

With an extended boom period on our doorstep, the industry must be prepared to reapply several lessons of simplicity and decluttering of vision and process. New thinking from different suppliers, and even different sectors, will complement IPD’s collaborative framework.

“What underscores the success of lean IPD is its need for strong relationships that create a collaborative framework to develop and deliver projects. This is fundamental, and for the model to work, trust is sacrosanct; when breached, the model fails.”

“Delivering projects with speed to market and sustainability credentials is the best chance we have if we’re to avoid a supply gap,” Yacoub concludes. “With a collaborative lean IPD model, we stand at the forefront of demonstrating, once again, how the mining and metals industry adjusts, adapts, and innovates for change.”