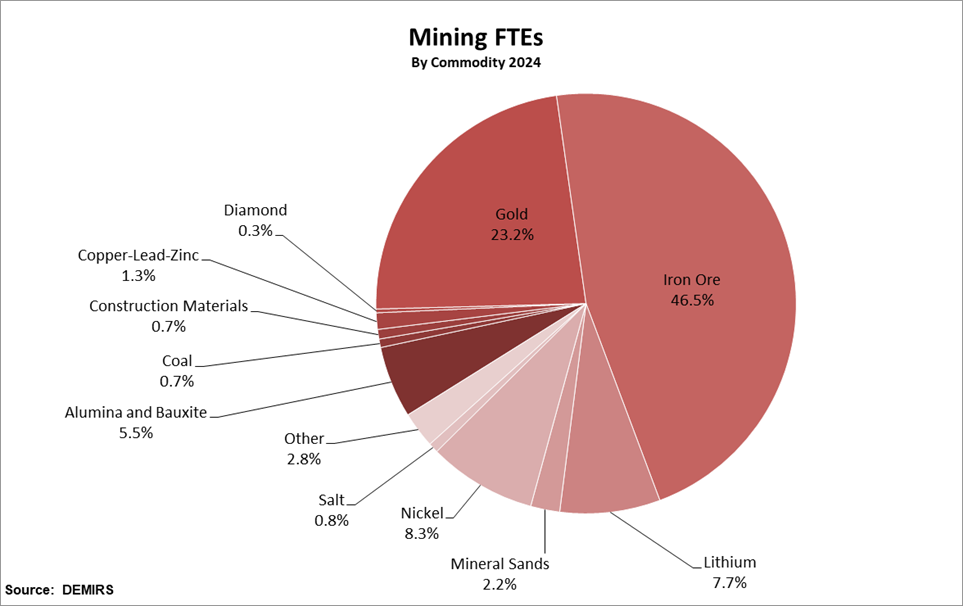

For eight years straight, employment in Western Australia’s (WA) mining industry has been climbing. Government data shows that in 2024, the region, which accounts for 47% of Australia’s total mining workforce, registered a record high of 135,693 on-site full-time equivalent (FTE) positions filled.

Iron ore, which is concentrated in the Pilbara, was responsible for the lion’s share of WA’s mining workforce (65,359 – up 4,500 FTE), followed by the currently booming gold sector (33,285 – up 3,000 FTE) in the Goldfields and mid-west.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Gavin Lind, CEO of the Mining and Automotive Skills Alliance (AUSMASA), which published its 2025 workforce skills plan Insights for tomorrow in August, says WA is expected to account for 40% of the nation’s resource workforce growth over the next five years, reflecting its huge share of the national industry.

This growth mirrors a wider trend across Australia’s mining sector where vacancies remain at record levels, surpassing peaks from the 2011–12 mining boom, with skills shortages widespread, according to the report.

On the ground, the situation is overt, says Steve Heather, managing director of WA-based MPI Recruitment.

“There is acute demand being witnessed in every technical discipline across mine geology, engineering and processing, with the underground environment the biggest driver for the significant demand lift,” he says.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataUnderground technical skills in particular are in “hot demand”.

“We can only see this getting tighter in the short-to-medium term; a big driver [is] the need to maintain very unique safety standards across the underground environment,” Heather says.

Lind also notes that “many traditional manual roles are evolving, creating new opportunities for upskilled professionals and technical newcomers in the mining sector”.

Recruiters of other roles say they are seeing demand for heavy duty diesel fitters, MC and HC truck drivers, mechanical trades, mining engineers with 3-5 years’ experience, open-pit mining geologists, highly experienced plant operators and underground charge-up operators.

Layoffs in open-pit operations in the region haven’t been enough to plug the gap – especially as open-pit mining skills are not easily transferrable in the short-to-medium term to underground mines, according to Heather.

“As a result, many traditional manual roles are evolving, creating new opportunities for upskilled professionals and technical newcomers in the mining sector,” he says.

WA layoffs

In response to continued low lithium and nickel prices, several mines in WA have gone into care and maintenance, including BHP’s Nickel West and West Musgrave projects; IGO’s Cosmos and Forrestania mines; and First Quantum’s Ravensthorpe mine. Nickel jobs have dropped by more than 3,200 (FTE).

“Employer reports indicate that WA’s mining workforce underwent significant changes during 2024–25,” says Lind. He points to BHP, which cut around 100 roles in its iron ore division, mainly targeting middle management and support teams, to streamline operations. The company’s nickel operations were also placed in care and maintenance, affecting around 800 operational jobs, although many were redeployed, he notes.

Rio Tinto also reduced its Pilbara workforce by around 500, driven by rising production costs. In February, the company cut approximately 120 in-house tradespeople roles from its Pilbara mine site services division, outsourcing the work to contractors as part of ongoing cost-cutting. The change is part of broader operational adjustments across Rio’s WA iron ore operations, which employ more than 17,000 people across 17 mines, says Lind.

Dani Tamati, founder and director of recruitment company THE resources HUB, says Tier 3 and Tier 4 mining companies involved in lithium and nickel are the ones really “feeling the pinch” and in response have made a raft of redundancies.

“The Tier 1s are not seeing that trickle down as much at the moment, as happened in the downturn of 2012,” she says.

Nickel and lithium only account for a small section of the WA mining industry, however, and so aren’t affecting the bigger employment picture in the region.

Tamati says that, along with the technical roles, her office is also seeing an influx of sales roles for mining services, with people trying to move from oil and gas into mining – which is not always an easy sector transition.

“The mining industry, in WA in particular, wants to ensure whoever we are bringing into the fold in a sales role already has a network and established connections and knows the products – it is not as easy a transition as some think.”

Migrant workers in WA’s mining workforce

So, how is WA’s mining industry filling roles? In part, through migrant workers, who have become essential to the mining workforce, says Lind.

“The number of skilled migrants has increased over the years, indicating an ongoing need for their skills,” he says.

In 2023, the Labor government launched a Skilled Migrant Job Connect Programme, which includes a subsidy to help skilled WA-based migrants access financial support of up to $7,500, and gain employment in occupations commensurate with their formal overseas qualifications, skills and experience.

Despite this, Harriet Banda, founder of Bantu Agency, an Australian-owned recruitment agency based in Perth and Zambia, believes the cost of placing migrant workers is still prohibitive. It can cost up to A$20,000 per candidate for training, acquiring an Australian driver’s licence, equipment and sponsorship, she says.

“The cost is prohibitive and there is no scale. Whether your business makes A$100m or $2m you still pay the 482 visa cost, which is unfair,” she says.

Heather agrees that the Australian Government is simply not responding fast enough to simplify the process of bringing in foreign technical workers.

His company has noticed more of the medium-to-larger scale companies with global operations starting to bring employees from outside of Australia to fill gaps and share knowledge.

“For these companies, offering their internal talent the opportunity for cross-country transfers, assuming the role is on the skills immigration priority list, is attractive,” he says.

Attracting candidates amid rising labour costs

To win candidates miners are deploying different strategies, including getting creative with financial incentives. Tamati says one of her clients implemented a sign-on and a six-month retention bonus, after which employees receive a monthly bonus for staying at the company.

“They were paying at the lower end for mechanical trades but with the retention bonus it was keeping their employees happy,” she says.

However, rising wages remain a sticking point for the industry. It is not hard to find a TikTok story about a migrant worker coming to the Pilbara with a few hundred dollars in their bank and leaving at the end of the year with tens of thousands.

However, consistently meeting high wages can be challenging for the smaller players, says Tamati.

“When the industry is booming, they have to offer the same sort of remuneration packages, share options and benefits to try and entice and retain workers,” she says. “They find it difficult when the bigger boys can throw money around and offer more perks.”

Attracting more women could support a more robust talent pool but parity figures have remained stubborn. Women comprise around 24.8% of the WA mining workforce, slightly lower than on a national level (27%) and up by 3.3% since 2021 but much lower than the national average of 48%.

AUSMASA data also shows that the mining industry still has significant gender pay gaps, with 95% having gaps in favour of men.

Many companies have set quotas, but Tamati doesn’t believe this is the right approach.

“It is merely setting up many of these women to fail within their careers, because they are literally a tick-the-box exercise,” she explains.

Apprenticeships: a bigger opportunity

Apprenticeships are another area where the mining industry could do better.

In its report, AUSMASA raises concerns about the level of mentoring provided to apprentices, noting that the national average completion rate for those who started studying in 2018 was 55.8% by 2022. This problem is exacerbated for international students who, because of visa regulations, cannot gain industry placement during their study period.

As a result, employers must invest in training international students once they are hired. AUSMASA says it has received stakeholder feedback calling for better-aligned visa regulations that would enable international students to acquire training and education equivalent to that of domestic students.

Tamati agrees apprentices are a missed opportunity in the industry.

“Apprentices are the first to be let go, yet they are the cheapest labour in the mining industry. Then when the next upturn happens, we don’t have any tradespeople, which is why we need to bring in sponsored people from the UK, Ireland and Africa, etc,” she explains.

What more can be done?

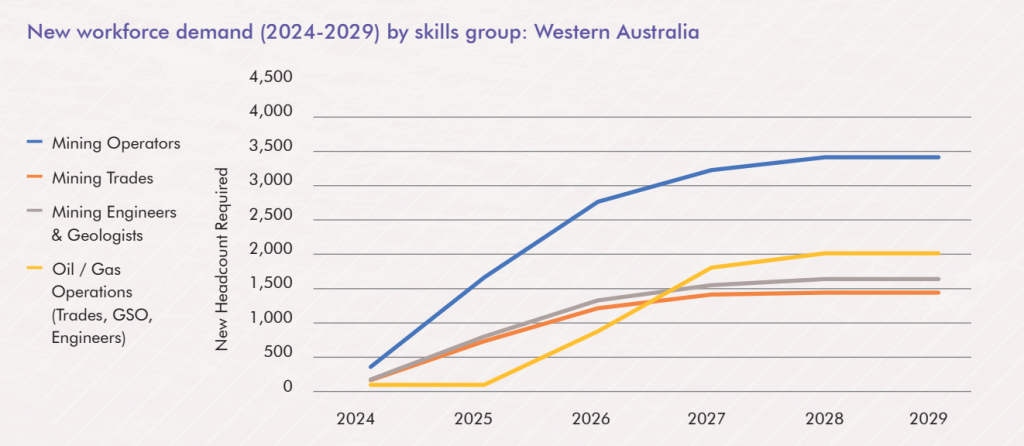

WA’s 48 proposed resource projects are expected to require more than 11,065 new workers by 2029. The highest demand will come from the mining sector, led by demand for mining operators.

Overall, the government estimates that the Australian mining industry will require an additional 56,000 workers by 2033, on top of the thousands of existing vacancies that remain difficult to fill.

AUSMASA’s main priorities are to help industry fill these roles, according to Lind, include running programmes in the areas including educational pathways, promoting diversity, technological advancement and digitalisation, workforce attraction, retention, and wellbeing, and sustainability and industry transformation.

However, many feel the government should do more. Tamati says that when it comes to the building and construction industry the government is doing a “really good job”, offering discounted trades qualifications and other incentives – but it could do much better for mining.

“It is not just the mining sector but the flow-on effect with suppliers and contractors and consultants,” she adds.

Heather agrees. “Right now, an awful lot of the heavy lifting is being left to the industry itself via its various associations and employer groups – but when you consider the huge contribution this industry makes to the Australian economy, why is the government not acting in its role of active industry partner?” he says.