As a leading global mining industry player in 2025, Australia recognises that to maintain its foothold and attract investment, it has to be a leader of the energy transition, a quick adopter of its sustainable technologies and a major producer of the critical minerals needed to produce them.

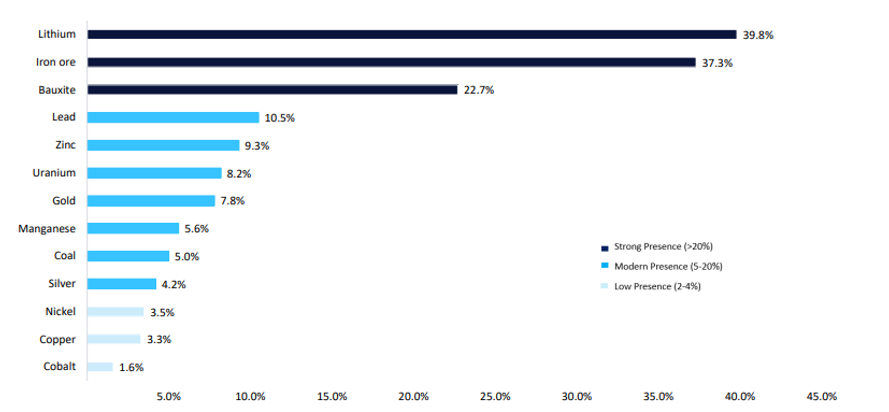

The country accounts for 36.4% of the world’s lead reserves, 29.4% of its manganese and 29% of its iron ore. It also has vast reserves of zinc, gold, cobalt, silver and bauxite, as the most resource-rich nation in the world, and ranks among the top three global producers for bauxite, lead and zinc. It is among the top global producers of an array of commodities, including lithium and iron ore, accounting for 39.8% and 37.3% of global output, respectively.

Australia’s mining industry bolsters the economy by contributing more than 12% to GDP and representing around 70% of export earnings. This includes a moderate presence in the coal market, accounting for 5% of global output.

A deep dive into a year’s worth of data and insights from MINE Australia’s parent company, GlobalData, reveals a country battling volatile commodity prices, operational costs and skills shortages but still managing to grow its mining industry.

Gayathri Siripurapu, senior mining analyst at GlobalData, notes: “Growth was evident across upstream mining, midstream processing and downstream clean-energy inputs, including battery materials, rare earth refining, green iron and low-carbon technologies.”

If anything, 2025 has made clear that how Australia weans its economy off its coal market dependency, navigates securing its critical mineral supply chain and overcomes commodity volatility will determine its future on the global mining playing field.

Critical mineral market expansion

Global decarbonisation, energy transition requirements and efforts by major economies, including Australia, to diversify their critical minerals supply chains away from China’s monopoly, drove the expansion of Australia’s critical mineral sector in 2025.

Demand for lithium, nickel, copper, rare earths, and manganese has grown, as they are key to the manufacturing of electric vehicles, renewable energy infrastructure, batteries, hydrogen electrolysers and defence applications.

Australia also made moves to secure its supplies in the long-term, including the signing of a landmark deal with the US in October to fortify global supply chains for critical minerals and rare earths.

“Australia retained its position as a secure, low-risk supplier, supported by strong environmental, social and governance credentials, a world-class mining, equipment and technology services sector and a highly skilled mining base,” says Siripurapu.

Federal policy support such as the Critical Minerals Strategy, a A$4bn Critical Minerals Facility, the National Reconstruction Fund and the Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive, assisted in strengthening investment confidence and encouraging downstream processing.

Production wins: lithium, iron ore, zinc and more

GlobalData expects Australia’s lithium output to rise by 2.7% in 2025 to 114.4 kilotonnes, continuing an upward output trajectory from 111.4 kilotonnes in 2024. It anticipates a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.2% to reach 147.3 kilotonnes in 2030, driven by the start of the Liontown Resources’ Kathleen Valley Project in July 2024 and SQM’s Mt Holland Lithium project in H1 2024.

Australia’s iron ore production is expected to grow by 1.4% in 2025, followed by a 2.8% CAGR during the forecast period of 2025-2030 to reach 1,108.7 million tonnes (mt). The ramp down at BHP’s Yandi mine, which is slated to close before 2027, caused output to flatten in 2024.

Zinc production is looking to pick up following four consecutive years of decline, according to GlobalData figures. It will experience a modest recovery in 2025, with projected growth of 1.6% to 1,133.8 kilotonnes. Projects that started in 2025 will drive output, including the Federation Underground, Endeavor and Woodlawn Expansion. However, GlobalData notes the rise is relatively small and unlikely to offset challenges in the wider supply landscape. It projects a decline at a negative CAGR of 2.3%, hitting 1,009.8 kilotonnes by 2030, driven by mine closures.

Manganese production experienced a major recovery milestone in May 2025, following disruption by Cyclone Megan in 2024. Consequently, GlobalData projects production to rise sharply by 8.7% to 4.7 kilotonnes in 2025. However, the scheduled closure of the Groote Eylandt mine in 2029 is anticipated to drive output down to around two kilotonnes by 2030.

Gold production is set to climb following 2025, from 10.2 million ounces (moz) to around 13.2moz by 2030, alongside key projects such as the Hemi Gold Project and as operational recoveries at established mines come online.

As for bauxite output, its data reveals flat growth in 2025 driven by Stage 2 expansion of production capacity at Metro Mining’s Bauxite Hills mine. Looking ahead, the country’s bauxite output is projected to remain relatively flat, with a CAGR of 0.8%, reaching 106mt by 2030.

Production challenges: copper, nickel and lead

GlobalData expects copper output to fall by 7.9% to 710.4 kilotonnes in 2025. The drop is largely attributed to the closure of the Mount Isa mine in 2024 and operational disruptions at key mines. However, output will pick up from 2026 as operating conditions normalise, hitting 1,073.2 kilotonnes in 2030.

The nickel market experienced global oversupply and weaker prices. This oversupply, which started in 2022 and is mainly from Indonesia, led BHP to curtail its Nickel West operations in December 2024, resulting in a projected 6.6% decline in mined output by 2026.

The scheduled closure of Potosi/Silver Peak this year and Rasp next year, which both have depleting reserves, in addition to a fire at the Century Tailings mine in 2024, which left it placed under care and maintenance, leave expectations bleak for 2025 lead output. GlobalData expects output to drop from 481.2 kilotonnes in 2024 to 466.8 kilotonnes this year and ultimately to 442.6 kilotonnes by 2030, due to planned closures of Rosebery in 2028 and the Cannington mine in 2029.

Winding down coal production and ramping up critical mineral output

Australia’s coal sector is a central pillar of its mining industry, boosted by Queensland’s skilled workforce and developed infrastructure, which contributes 90% of the nation’s metallurgical coal. The country’s coal output is expected to remain flat before growing moderately toward the end of 2030. This will be mainly due to operational improvements and new approvals, says GlobalData.

Production is forecast to rise from 465.3mt in 2025 to around 482.8mt by 2030, despite softening demand from China, as the country makes a strategic move to increase domestic production.

However, simultaneously, Australia is making efforts to ramp down its coal market. Approximately 24 coal mines are slated for closure up until 2030, and smaller mining industries in other states are making moves to produce low-carbon economies.

Although mining accounts for a relatively small share of Victoria’s gross state product, contributing around A$1bn–A$1.2bn annually, the state prioritised expanding its mineral potential through critical minerals development, new exploration projects, and stronger community engagement frameworks this year. It’s also one of the few jurisdictions to produce antimony, which is crucial for battery and defence technologies.

In early 2025, the Victorian state government launched its Critical Minerals Roadmap, detailing goals to attract investment in minerals such as antimony, zircon, rare earths and titanium and promote ethical sourcing standards and downstream processing.

The state is even intensifying rehabilitation programs for decommissioned coal mines, exploring ways to repurpose the Latrobe Valley, which was once the core of Victoria’s brown coal industry, for renewable energy.

Tasmania has continued its critical minerals drive, following the formalisation of its plans in the Critical Minerals Strategy, published in November 2024. In October 2025, the regional government signed a federal funding agreement to carry out a feasibility study for establishing a common user processing facility for critical minerals. The study will investigate processing opportunities in the northwest of the state, focusing on tin and tungsten. The initiative aims to reinforce the state’s role in Australia’s critical minerals sector by promoting value-added processing, new downstream industries and local job creation.

More broadly, Australia is in the third year of its Critical Minerals Strategy 2023-30, which targets A$500bn in export potential. New projects such as Liontown’s Kathleen Valley, Iluka’s Eneabba rare earth refinery and Arafura’s Nolans NdPr project reinforce this potential.

Australia’s AI and automation upgrade

It is becoming increasingly apparent that Australia’s mining operators will have to stay on top of emerging technologies if they are to remain competitive and meet growing demand for transition minerals throughout and beyond the energy transition.

Jack Kennedy, mining and deeptech investor at the venture studio and startup accelerator Founders Factory, says: “These technologies are making it possible to identify deposits faster, deploy capital more efficiently, and build operations that learn and adapt in real time.

“Where we’re heading is a sector that is more agile, connected and resilient, built on intelligent resource systems, AI, robotics, bio-innovation and ecosystem intelligence.”

Major miners, including Rio Tinto, BHP, Fortescue and Roy Hill, continued to scale autonomous haulage, drilling and rail systems, with autonomous fleets “accounting for more than half of haul truck movements in the Pilbara by mid-2025, delivering productivity, safety and cost benefits amid labour constraints,” says Siripurapu.

Meanwhile, Epiroc converted all 78 haul trucks at Hancock Iron Ore’s Roy Hill mine to autonomous operation using its original equipment manufacturer-agnostic LinkOA system.

Electrification progressed later in the year with BHP’s introduction of Australia’s first Cat 793 XE battery-electric haul trucks at its Jimblebar mine in December to reduce diesel usage and emissions.

Rising operational costs and skill shortages in critical areas

Despite productivity gains from automation, labour shortages across key areas such as mining engineering, maintenance, electrical trades, and automation continued to push wages higher.

High wages and inflation have led to rising operational costs. Mining wage growth averaged 5.3% in 2024, above the national average.

“Cost pressures were compounded by higher energy prices, consumables inflation, rising sustaining capex, and stricter safety and environmental compliance requirements,” says Siripurapu.

Although the industry displayed resilience overall, signs of financial stress began to emerge throughout the year. For example, the Burton coal mine in Queensland went into administration, BHP announced job cuts at Saraji South and Anglo American’s Queensland coal operations, and liquidity pressures at some mid-tier producers.

Equally, skill shortages in critical areas of engineering, drilling and heavy machinery slowed project ramp-ups, and are expected to continue into 2026.

“We’re seeing an ageing workforce and a lack of new entrants – many young Australians see mining as environmentally damaging or outdated, which is widening the generational gap and intensifying the skills shortage,” says Kennedy.

“When you combine that shortage with the tendency for large-scale projects to exceed budgets – often due to disconnected data, slow decision cycles and rigid project design – it’s clear the industry must adapt and change to meet such challenges.”