Australia is facing a critical inflection point for its largest export: iron ore.

Long the backbone of the country’s resources sector, iron ore and concentrates brought in A$124.5bn ($81.3bn) in export revenue in 2023–24 – more than any other commodity and nearly a fifth of the nation’s total exports.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

However, the traditionally-sourced iron ore market Australia helped build is now under threat. China, its biggest customer, is rapidly moving away from traditional blast furnaces and towards greener electric arc furnace (EAF) steel-making as it rushes to decarbonise. This shift means Australia’s traditional iron exports, and the earnings that come from it, looks set to decline.

Speaking at the 2025 Financial Review Mining Summit in May, Fortescue chairman Andrew Forrest said that without adaptation, Western Australia’s (WA) iron-heavy Pilbara region could become a “wasteland”.

Meanwhile, China’s move towards cleaner production methods has sparked interest and investment in the potentially transformative opportunity of green iron.

Policymakers and industry analysts alike see an opening for Australia to take advantage of this shift and become a major producer of green iron by capitalising on its mineral endowment and renewable energy potential.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataChina’s pursuit of green steel

Historically, China has been reliant on Australia for its iron ore, with WA alone supplying an estimated 65% of China’s imports in 2023, according to state government data.

However, the nation is making a hard pivot away from coal-based steel-making towards greener production methods. In July, the Chinese Government issued a decree requiring steel-makers to increase green energy usage in steel production, and the country has seemingly halted new permits for traditional coal-based steelmaking since early 2024, instead greenlighting EAF projects.

EAFs typically utilise renewable energy to power high-voltage electric arcs, which are used to melt scrap steel. The process limits carbon emissions by reducing the need for thermal coal for power generation and metallurgical coal for iron making in blast furnaces.

China now has enough EAF furnaces to produce more than 160 million tonnes (mt) of steel annually.

The issue here is that Australia predominantly produces hematite-based, rather than magnetite-based, iron. The former is typically used in coal-based blast furnaces, while the latter is better suited to EAFs.

As such, Forrest warned that China was likely to turn to magnetite from Brazilian or African mines to fuel its green furnaces, putting Pilbara hematite at a disadvantage.

To develop its own green steel-making industry, Australia has to work to access and process its magnetite deposits, which are lower-grade and require more treatment than hematite. While magnetite reserves exist in Australia, efforts to establish widespread processing capabilities for the material remains a capital-intensive challenge it has yet to solve.

“In Australia, producing green iron presents a multifaceted challenge – not just economic or technological but also geological,” Soroush Basirat, energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), tells Mine Australia.

Australia’s opportunity in hydrogen

The potential economic benefits of green iron are massive. A report by the Superpower Institute (TSI) estimates that Australia could export 10mt of the material by 2030, generating up to A$295bn a year – three-times the current export value of iron ore.

The most viable path to producing green iron in the nation is through green hydrogen (hydrogen produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy), which is used to strip oxygen from iron ore in a low-emission process called iron ore reduction. This creates direct reduced iron (DRI), also known as ‘sponge iron’, which can then be melted in an EAF to produce steel.

“While hydrogen has long played a role in direct reduction technologies – where part of the reducing gas is hydrogen derived from fossil gas – truly green iron depends on green hydrogen, produced from renewable sources,” Basirat says.

More investment into research and development is needed to further the industry. Simon Nicholas, lead steel analyst at the IEEFA, says the country already faces stiff competition: “Green iron requires green hydrogen, so countries that already have low-carbon power grids as well as high-grade iron ore have an early advantage and will likely compete with Australia as early pioneers in truly green iron.”

Nicholas highlights South Australia, with its magnetite deposits and renewable-heavy grid, as a natural early mover – but delays in hydrogen development and renewed gas investment threaten that lead.

“Unfortunately, South Australia is currently being led towards more gas and failing carbon capture and storage, which will see it miss out on the green iron opportunity that it was poised to lead,” he explains. “Although gas likely needs to be involved in Australian DRI projects at first, early use of green hydrogen needs to be prioritised and ramped up to replace gas in the medium term.”

He also argues for policy support. Current government subsidies do not prioritise hydrogen’s end use, leaving too much emphasis on expensive export models rather than domestic applications like green iron.

“A better path forward would be to target subsidies towards projects that will use green hydrogen for sensible uses – i.e. any sector that already uses hydrogen, such as fertilisers or explosives,” Nicholas adds. “This includes DRI-based ironmaking.”

Similarly, Basirat says realising green iron’s potential will take “coordination and commitment across industry, government and investors”.

Regulatory support for green iron in Australia

According to the TSI’s report, there are three main obstacles to green iron production in Australia: lack of financial support for early investors, underdeveloped infrastructure and an absence of a global carbon price, making green production less competitive.

“We can’t expect markets to fix themselves,” says Ingrid Burfurd, carbon pricing and policy lead at the TSI. “We need policy leadership to back early projects, close the cost gap created by the lack of an international carbon price and help lay the foundations for a globally competitive industry.”

However, ensuring Australia will have the demand certainty to justify strong investment in green iron is a big question for government bodies and mining companies alike.

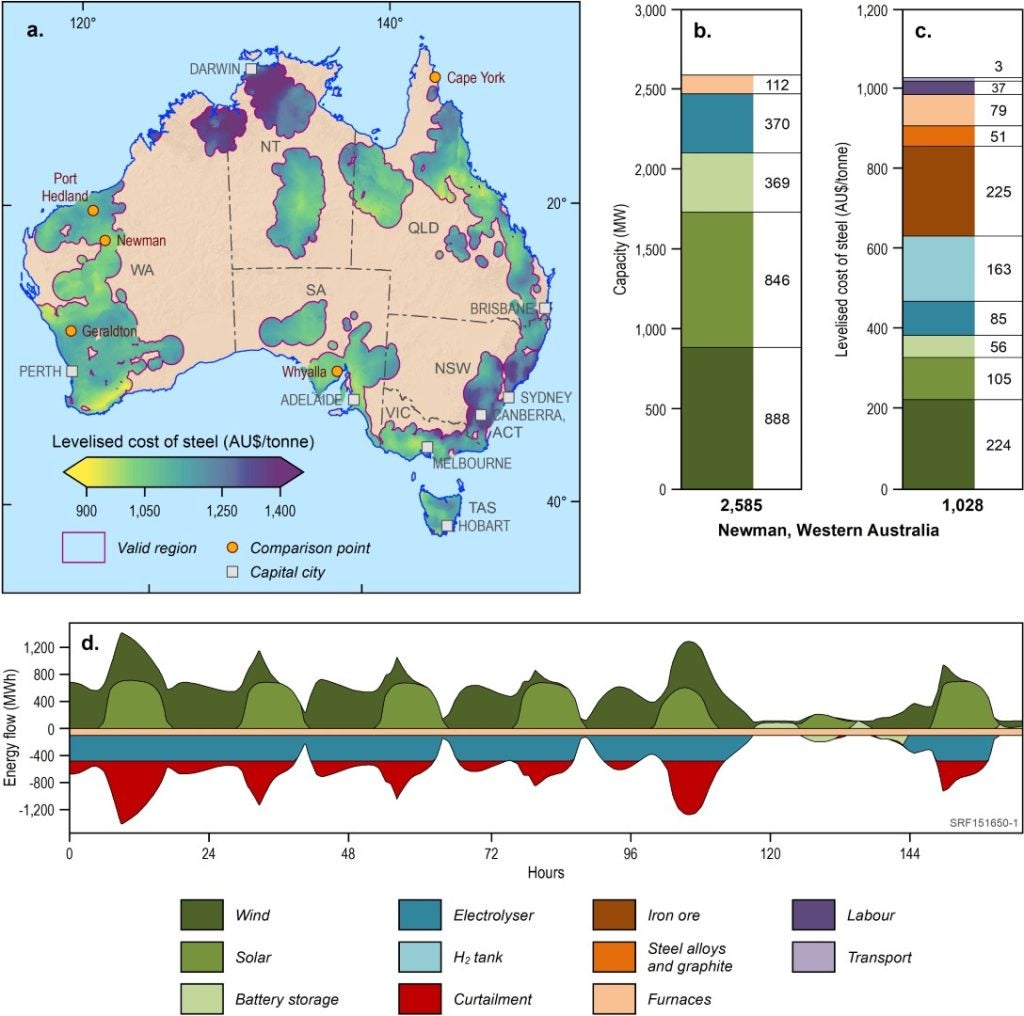

Some are attempting to provide an answer. For instance, researchers at Monash University and Geoscience Australia created the Economic Fairways Mapper, designed to identify low-cost regions for mineral, energy and groundwater systems by analysing energy flows, transport costs and ore availability.

“The transition towards green steel disrupts traditional steel supply chains, creating both opportunities and challenges,” Marcus Haynes, project lead at the Economic Fairways project, tells Mine Australia. “The opportunity is to move further up the supply chain and increase the domestic value-add on our raw materials. The challenge is that change requires large investments which, to be successful, must remain competitive as technology and conditions change around them.

“To optimally navigate the energy transition, and its disruption, we need to arm decision-makers with pertinent and timely information,” he adds.

Since its 2023 launch, Haynes says the platform has seen “strong usage” across government, academia and industry, with green steel models accounting for more than 20% of all simulations.

In February, the federal government took its first significant step, announcing an A$1bn Green Iron Investment Fund to support early-stage projects and supply chain development.

The fund was welcomed as a significant first step, but industry members have called for more investment to truly solidify Australia’s position, with hopes that this interest turns into real-world action, enabling Australia to stay ahead of the curve.

“At the current pace, it would take over 100 years to deploy the necessary renewables to replace 10% of Asian steelmaking with green iron,” Georgine Roodenrys, partner at Deloitte Australia, wrote in a report highlighting the challenges facing Australia’s green iron industry.

“Australia needs to accelerate the deployment of renewables and establish pragmatic policies that support both economic and environmental goals.”

Australia has the resources, the geography and the technical know-how to monopolise on green iron’s potential. Done right, the industry could triple the value of its iron exports, cut national emissions and position Australia as a key supplier in the global green economy.

However, as experts warn, this future won’t arrive by default. What it needs now is the investment backing and industry commitment to seize the opportunity.

As Basirat says: “Without swift and large-scale action, Australia risks falling behind other nations that are already moving decisively to capture opportunities in this emerging green iron market.”