“You can’t fight the geology; you have to follow it,” says Karol Czarnota, senior science advisor at Geoscience Australia.

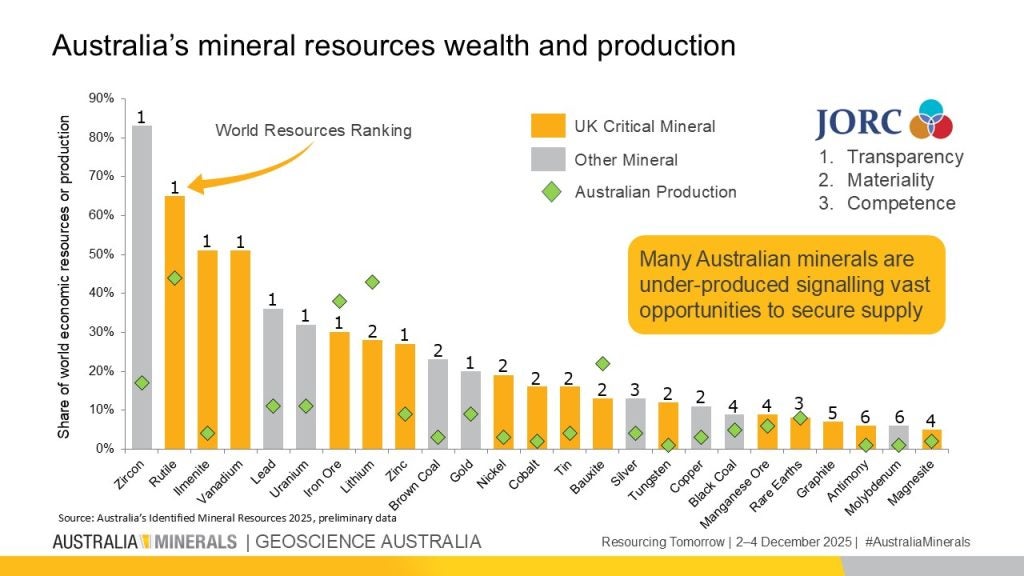

As the Australian Government’s national agency for geoscience, Geoscience Australia researches and tracks Australia’s geological endowment and commodity production. In its 2023 world rankings, it found that Australia was the leading producer of bauxite, iron ore, lithium and rutile globally, and ranked in the top four global producers of other commodities including gold, lead, manganese ore, rare earths, tantalum, uranium, zircon and zinc.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

However, its subterranean potential is far greater: Australia has the second-largest nickel reserves (after Indonesia) but ranks sixth in terms of global production. It also ranks third in copper reserves (after Chile and Peru) but eighth in copper production.

This is where Geoscience Australia comes in: the agency’s critical minerals data informs decisions around the best economic opportunities and most promising international partnerships. As the world repositions its supply chains around critical minerals, Australia could be at the centre.

“Australia has the periodic table of critical minerals,” says Czarnota, “and, because of the breadth of expertise across the mining sector, Australia is looking to progress industry around a lot of them.”

He points to the agency’s tracking of 599 critical mineral deposits across Australia, of which only 47 have operating mines, while 76% remain undeveloped.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThere is huge economic potential, and Australia knows it. The country’s mining sector already contributes 14.5% of gross domestic product from more than 300 operating mines, and the exports from these mines account for 61% of Australia’s overall export income. These 300 mines also provide direct employment to 300,000 workers, alongside indirect employment to another 1,100.

The Australian Government recognises that the transition represents a moment of mammoth strategic and economic importance. Last year, it launched the 35-year Resourcing Australia’s Prosperity Security initiative: a A$3.4bn ($2.25bn) investment led by Geoscience Australia, focused on accelerating the discovery and development of critical minerals and other resources.

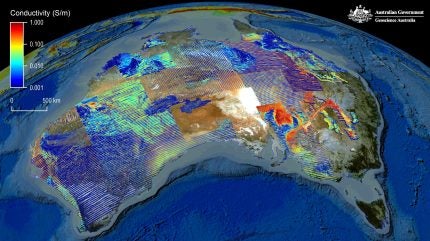

Geoscience Australia is working to achieve this goal across various geological mapping projects. These include the AusAEM survey, the largest airborne electromagnetic survey ever undertaken, which is gradually working its way across Australia at a line-spacing of around 20km.

“We take data sets and fuse them together to make mineral potential maps. They are like heat maps for where you should go and explore certain styles of deposits. We couple this with a whole series of technological economic assessments, so you can find the sweet spots,” says Czarnota.

As the critical mineral sector continues to reposition itself around supplies, Mining Technology speaks to Czarnota to hear more about Geoscience Australia’s work and its assessment of Australia’s place in the global picture.

Eve Thomas: What would you identify as the most pressing questions around Australia’s critical minerals right now?

Karol Czarnota: Australia is a supplier of critical minerals. You can sense the urgency around critical minerals at the moment – you could feel it at the recent Resourcing Tomorrow conference and also at the EU’s Raw Materials Week.

The elephant in the room now is financing: how do we secure long-term funding for long-term initiatives and guard against price manipulation? We have to think of all options, such as price floors and so on, and Australia has to consider that within the strategic context of its mineral reserves. In order to accelerate the supply from Australia, the urgent questions are around the financing component. Just recently, the government announced a revision of the environmental laws surrounding the federal component of the of environmental approvals, to try and accelerate projects.

ET: When it comes to actualising subterranean potential, where does, could and should Australia sit in the international picture?

KC: In terms of where we are, we are focusing on the original extraction of the ore and making the most of midstream opportunities. You can see it in lithium; in just in a few years, Australia went from producing almost zero lithium to becoming the world’s largest producer. When we want to, we can accelerate the production significantly. We are also seeing this with rare earth elements and the byproduct, gallium.

For these elements we are moving downstream, which is supported by Australia’s Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive. For Australia, it is about taking the next step and meeting our partners midway. This mid component is often the hardest. There is a lot of downstream metallisation and alloying, expertise within Europe, and a lot of products that are very niche, which need to have very specific designs. Meeting midway is a great opportunity for Australia in terms of partnerships for across the world.

ET: In terms of strategy, is it better for Australia to focus on increasing its production of a handful of critical minerals, or to have fingers in lots of pies?

KC: Australia has the periodic table when it comes to critical minerals, and because of the breadth of expertise across the mining sector, we are looking to progress a lot of them across industry overall. Government policies are supporting development of critical minerals, of which we have 31. They have been selected based on our partners’ needs, our geological supply potential and risk of supply disruption. Currently, we are seeing our partners invest around these supply pinch points. Overall, we are trying to advance the whole industry and support our partners with a reliable supply of the resources that are most critical to them.

ET: Geoscience Australia bases its findings on extensive and carefully collated data. What is the role of data collection and sharing in securing mineral supplies and in Australia’s international relationships?

KC: You can’t fight the geology, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t nurture it. The geological potential is as it is, but we need to understand it. There are locations that have geological diversity and potential, but it is still a great effort to discover those deposits. We make our data sets freely available; we don’t ask people to pay for it because we know that, by making them transparent and open, it provides that platform for others to build upon and maximise success – and it means that our companies are innovative, entrepreneurial and active. They go through and test many projects, and as a result, they discover more high-value deposits; 80% of Australia is under-explored, so what happens when you go exploring in a new region? It could be very remote, it could be undercover, it could be exploration of a new concept; for example, a lot of lithium deposits were found in areas that previously had gold and nickel mines. When you go into those regions, it is generally the largest deposits that get found early.

By providing that data – whether it is just raw data sets that you can use, or new concepts in terms of understanding the potential of an area – you are more likely to find the larger deposits first, which have the better economics and therefore provide that stability of supply that the world needs.

ET: What can politicians do to drive exploration in Australia and capitalise on Australia’s mineral reserves?

KC: We are seeing this happen already. There has been amazing investment, including the Resourcing and Prosperity initiative, which is a A$3.4 bn investment by the government. That is huge. It is unprecedented. We are looking at a great diversity of minerals. There is the whole periodic table and a whole level of complexity here, but we do have 35 years to get on with it. These resources are going to provide the pipeline of projects into the future, because it is a long-term game.

Now, part of that emphasis is on how we make the most of what has already been discovered. There are quite a lot of Australian projects queued up at the feasibility stage that are ready for investment and ready to progress. For Australian minerals, the point now is to get in early.

ET: What technologies are shaping the sector right now and which technologies is Geoscience Australia excited about?

KC: There are several ways by which you can sense geology, and there are lots of different properties that you can measure. Industry has been running on magnetics, gravity and geological maps for a long time; they have served us well, and we have got them to very high standards across much of Australia. We are still investing in those data sets and building them up, but there is a whole wave of new data now too.

One thing that we have done, which is super exciting, is the AusAEM survey. We started this about nine years ago: we fly an aircraft that generates an electromagnetic field (a secondary field within the earth) and we measure its decay, then we use that to make cross-sections of the conductivity of the earth down to between 300m and 500m in depth. We are now doing this across the entire country, with 20km spacing, and we have covered around 70% of Australia as of now.

It results in direct targets for companies to test, and importantly, it also de-risks that technique. When people talk about de-risking, they usually mean partially, but because we have flown across the geology, we can know whether that technique works, so we are seeing the uptake of this by industry in higher resolution. For example, there are places the flight line went across, where rare elements have been intersected in clays, and this technique has mapped the clays beautifully. A company can do a much higher-resolution survey, and accelerate its definition of the deposit rapidly through a technique that it was previously unsure would work. The technology for a lot of that was developed through a Cooperative Research Centre in Australia, and we have continued to invest in learning how to extract the information from it through probabilistic inversion.

That is at the very near surface, but we are also looking at depth. If you look between 70km and 300km, you can look at variations in the base of tectonic plates. What we found is that by mapping the variations in thickness, or by mapping the variations in conductivity of the tectonic plates, we can significantly narrow down the search space. One of the most significant decisions that an explorer makes is in the selection of the tenements. Where do they explore first? You can make a whole series of errors when you are exploring within that region and, if there is something significant, there is a high chance you will still find it. However, if you are looking in a place where there is nothing to be found, well, you can have the best team and you are still not going to find anything. Our large data sets fundamentally help explorers narrow in on the most prospective regions for discovery.